‘A piece of Pavo’s heart’ lost

Published 5:42 pm Saturday, May 31, 2014

- The youth enjoys skating at Pavo’s skating rink housed inside the school gym.

“Pavo, Georgia — the centre of a community favored by nature with a climate unexcelled and a citizenry of sturdy intelligent people, this place has grown in a few short years to be a solid town with strong backing,” was the headline on Friday, April 27,1906, in the Pavo Weekly Edition of the Times-Enterprise.

Trending

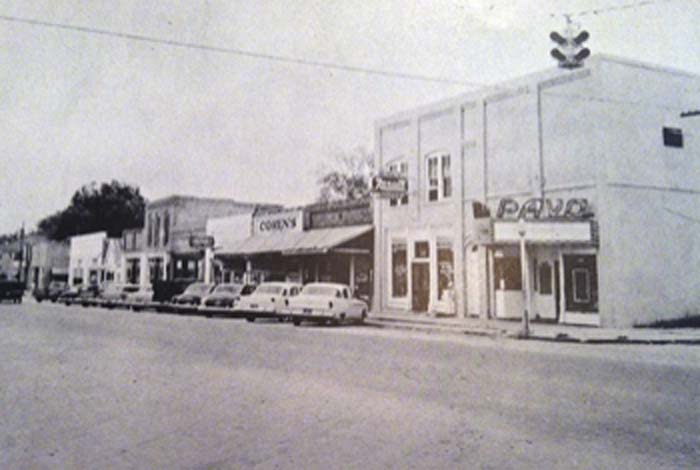

Today, Pavo’s biggest claim to fame is having country music artist Alan Jackson film the video for his 1999 hit song “Little Man” on Harris Street. The country tune, which bemoans the loss of mom-and-pop stores and the like, exemplifies the history Pavo.

Chartered on Aug. 17, 1903, Pavo was indeed a newly formed town when the Pavo edition of the Times-Enterprise was published. The town was beginning to make its mark in Thomas and Brooks counties as its split by the border.

In the 1906 article, it explained how vital Pavo was at the time.

Some of the popular stores included J.P. McGraw, a carrier of men’s furnishings and line of tobacco that opened circa 1905. The store also had a barber shop in the back that was operated by McGraw’s brother, Cary McGraw.

The Pavo Repair Shoppe opened eight years prior to the article’s publication and Pavo Drug Store opened in February 1905.

The Pavo Drug Company was managed by G. Gardener in 1906. He was born in Brooks County and received his education at the College of Pharmacy in Atlanta. He later went to Doerun. Gardner came to Pavo in February 1905. His assistant was John Beggs. The drug store was very well known for its soda fountain, “a real beauty.”

Trending

Pavo had a bank during the time that had the same president as the Bank of Thomasville, E.M. Smith. It opened in 1903 with $25,000. There was a 8,000-pound safe that had $100,000 as of 1906.

Pavo had a school at the time that taught grades 1-8 and had approximately 112 pupils. The article stated, “Pavo had a high school for some years and the number of its pupils had been steadily increasing. The school is situated at the end of Harris Street, which runs from the station up through the town, straight as an arrow and as wide as a boulevard. The school building stands like a lighthouse on top of a little hill.”

In Pavo’s paper, the Pavo Ledger, a Jan.12, 1917, article announced the opening of Pavo’s new High School. It stated, “The opening of the Pavo High School will take place Sept. 4. The local board has secured an efficient faculty for the coming season and it is expected the school will be greatly increased in attendance for the fall term.”

It is a popular theory that when Thomas County schools consolidated in 1960 that many of the county’s small towns, including Pavo, began a steady decline. At that time, Central High School opened in Thomasville, taking with it, as a 1986 Times- Enterprise article stated, “a piece of Pavo’s heart.”

Pavo has had three school buildings. One was torn down and the other one burned. The more recent building is located on McDonald Street. It served as Pavo Elementary School but is now called the Peacock Center and houses Pavo Civic Club events.

Anyone who attended Pavo Elementary School can tell you about one staple in its history that has not faltered. That is Ernestine Richardson, a lunchroom manager.

Richardson worked in the lunchroom for 35 years before retiring in 1968. Today, she is 93 years old and holds onto the memories of the students she served.

She said, “I really enjoyed it. Everyone was always so nice. You can just mention my name to anyone who attended the school and they will tell you I made the best cinnamon rolls. Everyone loved them.”

During her time there, she saw many changes. She started at the school in 1933 as a lunchroom worker before being promoted to manager, a role she held for 20 years.

“When I first started, there was an old coal stove we used and just one refrigerator,” Richardson said. “That was in the 1930s — and then later on, we got big freezers and then electric stoves. Things definitely improved for the school during those years.

“I had five ladies who worked with me in the lunchroom. After school, we would sell the students snow cones. With that money, we used it to fix up the dining hall at the school. We were able to put flowers on each table, draperies over the windows and even get a washing machine for washing our wash cloths at the school.”

Richardson worked under seven principals during her 35 years. She claimed they always had “really good days down there.”

After all these years, she still thinks about the students.

She said, “I got hugs every morning from the children. I miss them all so much.”

Records from Sept. 19, 1956, showed the Pavo Post Office served 4,200 people. It also stated the town had recreational actives, including a public park, swimming pool, skating rink, hunting and fishing facilities, and a movie theater. Doctors and hospital facilities were also available.

The records also had information regarding the general population and the citizens of Pavo. One said, “The attitude of people and workers towards industry is very good. This is a working area. We know what work is and how to produce.” It the time the population was at 1,200 people. The population was at 627, according to the 2010 census.

Education records showed that in 1956 there were 475 white Pavo students and 185 African American students. The number of high school graduates for that same year was 28.

Today, a Pavo native remembers the once sturdy town she still considers home.

Paula Jarrett, who lives in Thomasville, grew up with a farming family. She attended Pavo Elementary School from the first grade until sixth grade. Jarrett began elementary school in 1945, but not the building now known as the Peacock Center.

“The school burned right before I started school in 1945, so my first grade year was spent in a small cottage on the school grounds. I remember many of the children coming to school barefoot,” Jarrett said.

She also talked about life in Pavo.

“We mostly played outside,” she recalled. “There was a woman’s club that had books that they loaned, but it wasn’t really a library. It was through donations. The school gym was used as a skating rink and for square dances. A community pool was also available, but through my experiences, most farm children just played outside.”

Jarrett ended up moving away from Pavo for a couple of years to attend school.

She, like many other people, have their speculations as to why Pavo has declined so dramatically over the past few decades.

“When you take the young people out of a town, it declines,” Jarrett said. “Consolidation definitely made an impact on it.”

The town was also affected economically. It was once known for its vast crops, including watermelons, that were shipped out by railroad.

Jarrett also mentioned a used furniture store that brought many people into the town during the 1960s. With the closing of the school, decline in crops and businesses, jobs became scarce and people had to leave to find better economic conditions and jobs.

“I think Pavo is kind of making a comeback, though. The Air Purification building has brought some attractiveness back to the area. However, it is still a totally different life from what our grandchildren are now experiencing,” Jarrett waid.

Despite its struggles, Richardson has lived in Pavo her entire life.

She said, “I’ve always enjoyed living in Pavo. Everyone is very kind and mostly tends to their own business. It’s a nice little ol’ town.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: As part of a celebration of the Times-Enterprise’s 125th year, this is the 11th in a year-long series of Sunday stories about important people, places and things in the area. The next one will be published June 15.