Cnhi Network

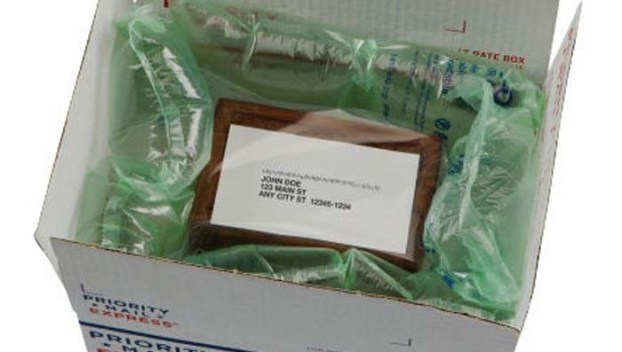

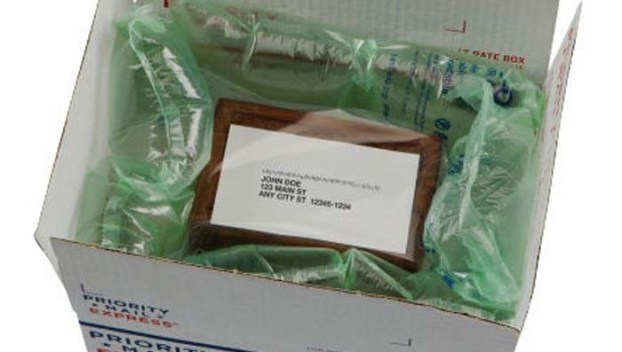

His mother’s ashes were lost in the mail. In his search, he’s found only frustration — and fury.

Donald Mink wasn't prepared for the call that came on Feb. 23: His mother had died in North ... Read more

Donald Mink wasn't prepared for the call that came on Feb. 23: His mother had died in North ... Read more