In light of Trump indictment, grand juror policies could be revisited in Georgia

Published 10:33 am Friday, August 25, 2023

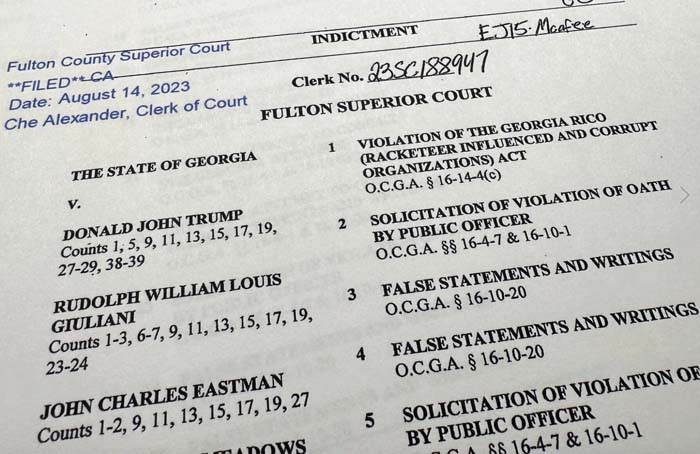

- THE JURY’S FINDINGS: The indictment in Georgia against former President Donald Trump is photographed Monday, Aug. 14, 2023.

ATLANTA — Georgia’s law requiring grand juror names to be included on indictments could make its way to lawmakers’ desks for a rewrite when legislators meet for the next legislative session in January.

The law became spotlighted after the Aug. 14 high-profile indictment against former President Donald Trump and 18 others by a Fulton County grand jury for alleged election interference.

The Fulton County Sheriff’s Office said it was made aware when threats against some of the 26 grand jurors whose names and personal information, including their purported addresses and social media accounts, were posted on websites of that appeared to be Trump-supporting.

“We take this matter very seriously and are coordinating with our law enforcement partners to respond quickly to any credible threat and to ensure the safety of those individuals who carried out their civic duty,” the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office stated Aug. 17.

CNHI reached out to at least a dozen of the grand jurors for comment but did not hear back.

Speculation made its rounds on social media that the Fulton County Superior Court erred in not redacting the jurors’ names before making the indictment public. However, the practice of publishing grand juror names is standard in Georgia — something several law professors and lawmakers said they weren’t aware of until the Trump indictment in Georgia.

“I actually don’t know where that practice comes from (I didn’t realize it existed until last week),” Caren Morrison, associate professor of law at Georgia State University, said in an email.

Added Democrat State Rep. Ruwa Romman: “I did not even realize that was a thing in Georgia. I guess a part of me always assumed that those names are protected and then I found out that they’re not and that was a shock to me personally.”

Pete Skandalakis, executive director of the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia, said he plans to bring forth some proposals to lawmakers regarding revisions to the juror name publication concern and other related proposals.

In most states, such as Alabama and Tennessee, only a designated foreperson chosen by the jurors signs the indictment, as with federal cases. The foreperson must sign onto the indictment with the consensus of the state’s designated threshold of jurors.

Some states allow prosecutors to request that juror names be available only to attorneys involved in the case.

“I think it’ll be up to the Georgia legislature how they want to decide it, but I plan to have those conversations with legislators,” Skandalakis said.

A look into Georgia’s grand jury indictment process

A 1914 case, Willerson v. State of Georgia, became pivotal in Georgia’s grand jury indictment process and interpreting the indictment form.

In that case, a Murray County Superior Court grand jury presented charges against the defendant, Sid Willerson, for the selling of alcoholic beverages. The indictment bill was signed by the jury foreman and Willerson moved to quash the presentment of the charges from the grand jury on the ground that the names of the grand jurors did not appear on the bill, despite there being a section on the form for their names to appear.

Willerson was ultimately convicted and later appealed to the Court of Appeal in Georgia, questioning the validity of an indictment where the grand juror’s names were omitted from an indictment.

The Appeals Court sided with Willerson, stating that listing the grand juror names on the indictment would be a method of showing compliance, such as for the requisite number of grand jurors to return an indictment and the composition of the grand jury.

Some cases since 1914, however, have argued that the omission of grand juror names should not make an indictment unauthentic.

In one case, it was noted that grand juror minutes could be made available to show grand juror names and participation. But most courts in Georgia have ruled that name omission from an indictment is a “fatal defect,” according to a case study provided by Skandalakis.

“The defendant has a right to know who’s sitting on the grand jury so (that) they could challenge (that) any grand jury members should they have been disqualified, you know, for not being properly qualified,” Skandalakis said.

Georgia’s code section 17-7-54 sets the standard for every indictment form.

The form requires the name of the county of the indictment, the name of the person being charged, the charge(s), “to wit” the persons bringing the charges and the form is to be signed by the jury foreperson.

“Because the language is ‘to wit,’ the grand juror names need to be on the indictment,” Skandalakis said. “And Georgia has no mechanism at this point for how we can can go before a judge and say, ‘Please, for due cause let’s keep these names sealed.’”

While at least 16 jurors must be present for all juror discussions, 12 votes are needed to move a case or indictment forward. Indictments, however, do not specify which jurors voted for or against, and the names of those who weren’t present for the vote are crossed out on the indictment.

Skandalakis said it’s customary for jurors to be informed on how indictment forms work and that their names will appear on the indictment.

“So there is an awareness that their names will be subject to public scrutiny — plus they’re sworn in and open court,” Skandalakis said “Every grand jury, every jury that comes into open court, and they’re sworn in right there in open court. Everything has to be done in open court.”

“But whether or not they understand completely, I don’t know. But I think most people understand it’s a public service because that is reiterated a number of times,” he said.

A juror’s concerns about their name being public isn’t a likely reason for the juror to be dismissed or excused from a case, but a judge could consider such concerns, Skandalakis said.

“But the issue that we have in this country is some people simply don’t want to serve on grand juries and juries. They just don’t want to take the time out of their schedule to sit and our entire process based upon citizens coming into the criminal justice system and serving,” Skandalakis said. “(Our system is) average citizens that come in and serve, and if everybody’s trying to get out of jury duty, that’s going to create a huge problem for not only defendants in the state but for litigation in general.”

Romman said she is open to Skandalakis’s plans to revise the grand juror indictment law to provide some juror protections, while allowing public transparency in the court system.

“I do think that the public has a right to know what their government is doing. However, in a situation like (the Trump indictment), if it means that somebody’s life is in danger, that somebody can be seriously hurt, etc. It’s important to find a better balance, and that’s what I always tend to err on the side of is, you know, is a good, balanced approach to this. and so that’s what I’ll be looking at moving forward.”