Dialing up help for mental health issues about to take a big step forward

Published 4:20 pm Monday, June 13, 2022

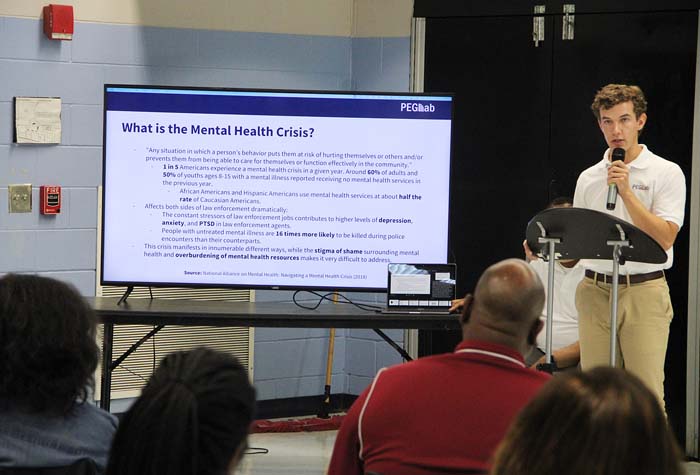

- Zachary Harris discusses mental health issues and crises Saturday at the Marguerite Neel Williams Boys and Girls Club.

THOMASVILLE — Help for mental health issues could be just a phone call of three digits away starting next month.

The Thomasville chapter of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity sponsored a mental health awareness campaign Saturday at the Marguerite Neel Williams Boys and Girls Club, and one of the highlights was the announcement of the 988 crisis line.

“It’s so important to get the word out into the Thomasville community and we want to expand much further than this,” said Marvin Dawson of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. “We just want to get the word out about mental health because this is a very important issue. There is so much going on, so many people are losing their lives. They’re taking their lives, they’re taking other people’s lives.”

Beginning July 16, 988 goes live nationwide, said David Sofferin, director of public affairs for the state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

What 988 will do, Sofferin said, is connect people to suicide prevention and behavioral criss resources.

“Anyone in the United States can call 988 and talk to a trained staff member 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he said.

Speakers included several from the field of academia, Thomasville native and director of PEGLLLLab at the University of Virginia’s Batten School of Public Policy and Leadership Brian Williams and Ernie Stevens, a former San Antonio, Texas, police officer.

Stevens was featured in the documentary “Crisis Cops,” which followed Stevens and his partner as they responded to mental health crisis calls. The documentary has been shown to thousands of local law enforcement agencies.

“Most people did not join the police department with the desire and the knowledge to answer mental health calls,” Stevens said. “What I found out quickly is I was not prepared to respond to mental health calls at all.

“I had no idea the opportunity law enforcement was missing when it came to responding to mental health calls,” Stevens continued. “We were not equipped. This was seen as a social issue. We weren’t doing a good job of that at all.”

Stevens also is working on the aftermath of the Uvalde, Texas, school mass shooting.

Stevens said he wanted to make his training and the lessons he and his partner learned available for the rest of the San Antonio department and neighboring municipalities. The documentary is also available for screening by local law enforcement and municipal agencies.

Having a mental health response team is the future of policing Stevens said. He said there has been a shift in police funding to place an emphasis on mental health.

“Changing the response from 911 to the response for crisis calls is something that is way overdue,” he said.

San Antonio now has several programs of co-responders, including one funded by a several hospitals. They also have identified the 100 most frequent individuals who go in and out of the acute care health system.

“We try to get ahead of the 911 call,” Stevens said. “A lot of times they don’t have access to a doctor. They don’t have transportation. If we can get to a patient before a 911 call, a cost savings and better care for these patients.”

Lindsay LePage, a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia, noted that more than one in five adults experienced mental illness in the last year. Of that, 19% are anxiety disorders and 21% are experiencing homelessness.

LePage also cited studies showing 37% of people in state and federal prison and 44% in local jails have a diagnosed mental health condition.

Mental health is also a critical problem among youths. One in three young adults 18-25 experienced a mental illness problem and among those ages 6-17, 17% had a mental health disorder.

Also, 50% of all lifetime mental illnesses begin by age 14 and 70% of youth in the juvenile justice system have at least one mental health condition.

Of the juveniles diagnosed with a mental health condition, only half received treatment.

LePage added the suicide rate is up 35% over the past three years. It is the leading cause of death for people incarcerated and is the No. 2 cause of death of law enforcement officers.

“People don’t have to suffer in silence,” she said.

Zachary Harris, from the University of Virginia’s PEGLLLab, said mental health issues can stem as a result of racial trauma, social media use or drug addiction.

“The one unifying factor about mental health issues is that they affect everyone,” he said. “Often these crises go unnoticed. Mental health has an impact on everyone, no matter who you are, where you are or where you’re from.”

Harris also pointed out that people suffering from a mental health crisis are 16 times more likely to be killed in a police encounter.

“When you look at law enforcement and mental health, the two impact each other on both sides of the issue,” he said. “We want to intervene with mental health issues before they become a crisis.”

Harris said there needs to be an overlap so groups such as the police department and the sheriff’s office can work with Georgia Pines, Archbold Medical Center and the Georgia Crisis and Access Line to address mental health issues before it results in a crisis. The Thomas County Dispatch Office has handled at least 750 mental health calls a year since 2017.

Dr. Seong Kang of New Mexico State University alluded to studies on the deleterious effects of social media on teenagers. They now have less in-person time with others and often question their identity and self-worth. And, instead of feeling more connected, they’re actually getting lonelier.

Kurali Grantham of PEGLLLLab said that 16% of Blacks in the U.S. reported having a mental illness in the last year. That equates to 7 million people — more than population of Chicago, Houston and Philadelphia combined.

Blacks have an inadequate access of health care and delivery of care, Grantham said, as a result of structural, institutional and individual racism.

Also, 11.5% of Blacks remain without health insurance, as opposed to 7.5% of whites, Grantham said.

Part of the mission of Saturday’s event was to remove the stigma of seeking help for mental health problems, Dawson said.

“That’s one of the first things that happens is people deny they need the help,” he said. “It’s important for us to remove that stigma for folks who feel like they don’t need help when they really do.

“It’s for everybody,” Dawson added, “but particular the Black community. We need the Black community to come out and say, ‘it’s OK to say I need help and point me in the right direction to get that help.’ And we just want to let them know we are here for them.”

The soon-to-open 988 line could be crucial. In August 2019, Federal Communications Commission staff released a report recommending 988 as a three-digit code for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The FCC worked with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Department of Veteran Affairs, and the North American Numbering Council.

Once 988 goes active, callers will be put in touch with “somebody who can walk in your shoes,” Sofferin said.

Those who dial 988 can call, text or online chat with help. Questions can be asked at 988GA.org too, Sofferin pointed out.

“We don’t want to see people waiting until there is a full-blown crisis before they call 988,” he said.

Sofferin also noted how he is in contact with the state Department of Agriculture every day on mental health issues.

“I never thought I’d be working with the Georgia Department of Agriculture,” he said. “I am on the phone with them almost every single day about farm stress. We are losing farmers to suicide every day.”

Sofferin said the GCAL (Georgia Crisis and Access Line) app can be downloaded for text or chat and is available 24/7.

Dawson said they plan to hold another such awareness campaign in the fall.

“We just want to do our part to make a difference in our community and continue to open those lines of communication, so we can move forward in a positive way,” he said.