The Great Divide: Election exposes rural, urban chasm

Published 10:00 am Sunday, December 9, 2018

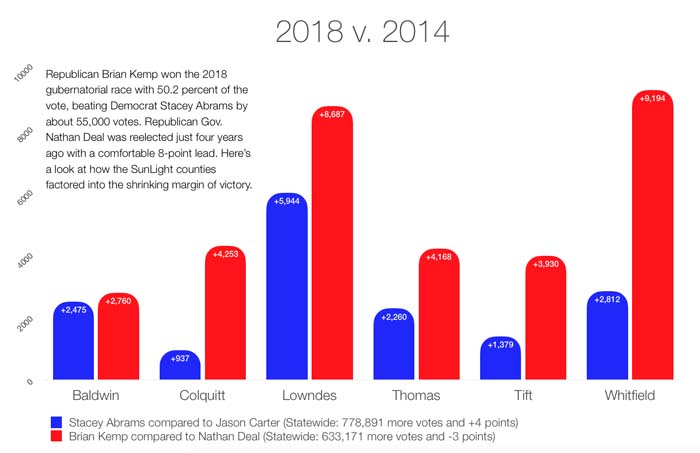

- A graph showing the voting difference between the 2014 and 2018 Georgia gubernatorial races.

ATLANTA — Georgia voters tapped Republicans for every statewide office this year, just as they have for the last decade.

Conservatives finished off the clean sweep with two runoff contests last week that kept the Secretary of State’s Office and the entire five-member Public Service Commission in Republican control.

But beneath the surface of those high-level Republican victories was a shifting political landscape that yielded the tightest margins of victory in decades and ousted several Republican lawmakers in the Atlanta area.

Republican Brian Kemp, who had President Donald Trump’s backing since the primary, won the governor’s race with about 1.4 percent of the vote – a difference of just 54,723 votes. It was the state’s closest gubernatorial contest in 50 years.

Kemp campaigned almost exclusively in rural counties, where he succeeded in running up the score in the state’s most conservative counties – even outperforming Trump in some places.

Stacey Abrams, his Democratic opponent, meanwhile was buoyed by support from urban and suburban Atlanta counties, although turnout fell short of what was needed from the metro area to tilt the statewide outcome in her favor.

When the dust settled, the midterm exposed a deepening divide between the state’s urban and rural communities.

The down-ballot races revealed the gulf more plainly: Democrats gained more than a dozen Statehouse seats in metro Atlanta, but lost three seats in rural districts. A Marietta Democrat, Lucy McBath, also defeated U.S. Rep. Karen Handel, who had just overcome a Democratic challenger in last year’s nationally watched special election.

Alarm bells

Abrams, who ran as a progressive Democrat, had been encouraged by the 200,000-vote gap that existed four years ago between Republican Gov. Nathan Deal and Jason Carter, who ran as a moderate Democrat.

She saw a shrinking margin of victory for Republicans since 2006, when Sonny Perdue was reelected by nearly 20 percentage points – a difference of nearly 419,000 votes.

The Atlanta attorney and former House minority leader, who would have been the nation’s first African-American female governor, slashed a sizeable deficit down to just 55,000 votes.

“It seems to me, from the Republican side, this should have the alarm bells just ringing violently and the sirens screaming at you that you need to do something,” said Charles S. Bullock III, a political science professor at the University of Georgia. “If you don’t, you can’t hope to continue to win statewide.”

The base Republicans have counted on for decades is shrinking, Bullock said. A broader, more encompassing message will be needed to continue winning these state-level races, he said.

“Where they do best are rural areas. Rural areas aren’t growing. They do best among older voters. Older voters are dying. They do best among white voters. The growth is in the minorities,” Bullock said.

“What it means for the Republican Party is that they’re going to have to really seriously change their message,” he added.

Two-thirds of Georgia voters were white in 2010, according to analysis from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. That decreased to 64 percent in 2014 and then down to 61 percent two years ago. In this year’s midterm, they represented 59 percent of the electorate.

But the electorate was also older this year, according to the AJC analysis. About 52 percent of voters were older than 52, which is a 5 percent jump from two years ago.

Rural, small-town white Georgians make up 26 percent of the electorate, and 82 percent of them backed Republican House candidates, according to the Associated Press. Suburban whites – 68 percent of which favor Republicans – comprise another 30 percent of voters. About 52 percent of urban white voters, meanwhile, lean to the left.

All this talk of a growing rural-urban divide is not just unsettling for Republicans, though.

“Rural Georgia needs help, and if we are moving into a future that is going to be rural Georgia versus Atlanta, Atlanta is going to win and we’re going to lose,” said Bardin Hooks, a 38-year-old Americus attorney.

Hooks just ran as a conservative Democrat to replace Rep. Bill McGowan, a Democrat who decided not to seek reelection after one term. Hooks, who is the son of a powerful former state senator, George Hooks, lost to former state Rep. Mike Cheokas, a Republican who narrowly lost the seat in 2016.

It was one of the three legislative seats Democrats lost in rural Georgia. The other two were in the Athens area.

Hooks said he found himself contending with the nationalization of even local races like his south Georgia contest.

“It used to be, when I was coming along, you’d have people say, ‘You should vote for the person on a local level and vote for the party on the national level.’ And now that doesn’t exist anymore,” Hooks said.

SunLight

The much-touted blue wave, though, crashed into that red wall Republicans promised.

In the SunLight Project coverage areas, which include Lowndes, Thomas, Tift, Colquitt, Baldwin and Whitfield counties, Abrams drew thousands more voters to the polls than Carter managed just four years ago. All of these counties – with the exception of Baldwin County – have been reliably red.

Yet, Abrams commanded a slightly smaller share of the vote in the county-level matchups in the SunLight Project areas when compared to Carter.

For example, Abrams had nearly 2,300 more votes than Carter did in Thomas County, where Abrams campaigned multiple times. Yet, Carter ended up with nearly 40 percent of the vote there four years ago – about 1.5 points better than Abrams.

That’s because Kemp had been working hard on the south Georgia county too, racking up nearly 4,200 more votes than Deal did four years ago.

“Her campaign brought out a lot more voters, but it also brought out a lot more Republicans in reaction to her,” said Mark Anderson, who chairs the Thomas County Democratic Party, referring to local turnout.

“Dispute our efforts, the Republicans turned out more than the Democrats, and I think that’s the story of the election,” he added.

While Abrams whittled away at the historical margin, Kemp worked to fire up conservative voters in rural and midsize GOP strongholds, such as Thomas County.

In some small, rural areas such as Colquitt County, Kemp even outperformed the ultimate Republican firebrand: Trump.

The county’s representative, Rep. Sam Watson, a Republican from Moultrie who chairs the rural legislative caucus, said he was puzzled by the turnover in the metro area, where the economy has flourished under Republican state leadership.

But he still thinks a rural-focused campaign will continue to have its political appeal.

“It’s cool to be rural at the Capital these days,” Watson said. “So if you want to pass a piece of legislation, you put some kind of rural Georgia initiative in it and you’re going to get a lot of bipartisan support.”

Watson said he doesn’t see that changing. He is vice chairman of a two-year-old legislative council that has put a spotlight on rural woes, such as a lack of high-speed internet connections and stagnant local economies.

Kemp’s focus on rural Georgia will just accelerate those efforts, Watson said, and rural voters will remember that in four years.

Jill Nolin covers the Georgia Statehouse for CNHI’s newspapers and websites. Reach her at jnolin@cnhi.com.