Beyond Sandusky: Penn State Center aims to help prevent similar tragedies

Published 3:00 pm Wednesday, June 28, 2017

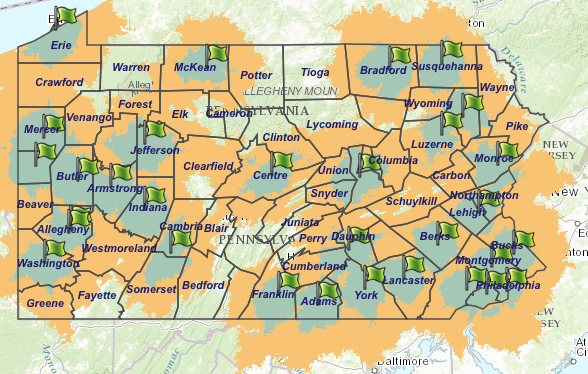

- This map shows how the areas in Pennsylvania within a 30-minute or a 60-minute drive from one of Pennsylvania's 31 Children's Advocacy Centers, facilities with staff specially-trained to interview children believed to be victims of sexual assault.

HARRISBURG, Pa. — Penn State is preparing to open a new $11 million Center for Healthy Children this summer with a mission to research how to best treat and prevent child abuse.

If all goes according to plan, the center will open in September, Penn State spokeswoman Monica Jones said.

Trending

It’s part of the wide-ranging response the university has made in response to the horrific child sex abuse scandal involving former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky and the subsequent cover-up of the allegations by Penn State administration.

The center is being funded with a $7.7 million federal National Institute of Health grant, and $3.4 million in Penn State funds.

The opening of center is the latest milestone in what has been a series of actions that began shortly after the Sandusky scandal came to light. In 2013, Penn State hired Jennie Noll as part of a plan to create 12 positions to create what has since been called the university’s Child Maltreatment Solutions Network.

“That’s a big expense and that’s in perpetuity,” Noll said. She came to Penn State from the Cincinnati’s Children’s Hospital. Before her stint in Cincinnati, she’d worked at the National Institute of Health.

The effort is supported, in part, by $12 million of the $60 million Penn State paid the NCAA over the university’s handling of the Sandusky cover-up.

A settlement in a lawsuit filed by state Sen. Jake Corman, R-Centre County, dictates that the Penn State fine stays in-state. The remaining $48 million was placed under the control of the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency. Most of that money is being used to fund new or help existing Children’s Advocacy Centers, facilities where specially-trained medical and law enforcement professionals interview and examine children believed to be victims of sexual assault.

Trending

Researchers at the Center for Healthy Children are consulting with those who work on the front-lines responding to abuse allegations to make sure their research is hitting areas that matter, Noll said.

One of the early focuses of research will be to develop a formula to determine what is a manageable number of cases for social workers in child protection agencies.

This has emerged as one of the looming topics of controversy over the state’s legislative response to the Penn State child sex abuse crisis. The state changed the definition of child abuse and greatly increased the number of people required to report suspected cases of abuse. That led to a tsunami of reports of alleged abuse. The state and counties didn’t invest extra money to add more caseworkers, fueling concern among advocates that in the tidal wave of complaints caseworkers are missing signals of serious abuse.

Child protective services agencies received more than 12.5 calls a day in 2016 with 44,359 cases of suspected child abuse reported to them. Of those, only 1 in 10 reports was substantiated.The protective services caseworkers were able to document that abuse occurred in 4,597 cases.

Five years ago, when the state got 24,615 reports of child abuse, caseworkers were able to substantiate 1 in 7 allegations.

The research is intended to provide lawmakers with a real guide to inform them about how much resource needs to be spent to adequately deal with the state’s child protection crisis, she said.

Noll said that much of the effort to combat child mistreatment has been made with little quantitative analysis done to determine if it’s working until years later when the youths grow up and either thrive or don’t.

Their aim is to use research to determine if what’s being done works and if it doesn’t find an alternative that will pay off better. Some of the most important work will be in trying to figure out what works best to prevent child abuse before it happens, Noll said.

“That’s why I came to Penn State,” Noll said. “to solve problems that move the needle.”

Once they identify models that work in Pennsylvania, they would expect to see it replicated in child protection agencies across the country, she said.

The research is an important component of the state’s response to the child abuse problem, said Delilah Rumburg, chief executive officer for the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape. Advocates who work with victims of sex assault already use programs supported by evidence, she said.

“We feel confident that they are promising” tools to help victims, Rumburg said. But, rape crisis centers don’t have the resources to invest in research to match what’s underway at Penn State, she said.

“We have a long way to go on prevention,” she said. “We are turning a corner because of these heinous crimes” at Penn State.

David Heckler, who chaired the state’s task force on child protection, said that the research is important to help compensate for the real-world strains on the child protection system.

“It’s some overworked social worker who initially confronts a lot of these situations,” Heckler said. That means that if the facts of the case are obvious, the abuse will likely be identified quickly.

“If someone jumps out of a bush and rapes someone, then you’re off to the races,” Heckler said.

However if the facts are murkier, it’s more likely that the abuse might go overlooked.

“You’re not going to solve that problems with a stroke of a pen in Harrisburg,” he said.

The Penn State research will help tremendously, he said.

“We’re really excited about what Dr. Noll is doing, It’s hard to assess if you’re doing good things,” Heckler said. “There’s always skepticism about whether grants are doing anything more than spending money.”

Heckler now chairs the committee created by the state Commission on Crime and Delinquency to oversee the $48 million from the Penn State fine.

His experience with the task force on child protection convinced him of the importance of adding Children’s Advocacy Centers across the state.

“If they had a CAC in Centre County” when the first Sandusky victims came forward, “it would have prevented 10 years of victimization, Heckler said.

The Children’s Advocacy Center opened in Centre County in 2014 -– three years after Sandusky’s arrest. It’s one of 11 Pennsylvania has added, increasing the state’s inventory of such facilities by 50 percent in just the last three years.

When the committee began its work in 2013, there were 20 Children’s Advocacy Centers in Pennsylvania, including one in Lawrence County and one Northumberland County. Children in one-third of the state lived more than an hour way from one of these facilities.

Since then, 11 Children’s Advocacy Centers have been added, including facilities in Cambria and Mercer counties. Along the way, the Commission on Crime and Delinquency handed out 44 grants worth $3.3 million in 2015 and another 42 grants worth almost $2 million last year. In addition to the advocacy centers, some of that money went to rape crisis centers and other groups serving survivors of child sex crimes.

Heckler said the pace at which the money is being released jibes with the intent of lawmakers when they determined that PCCD should oversee the funds. Act 1 of 2013, which funnels the money through the commission, stipulates that no more than half of the settlement funds can be spent in the first five years.

But now only about one-sixth of the state, very rural portions of central Pennsylvania, are more than an hour’s drive from a Children’s Advocacy Center.

Heckler said that as the state adds Children’s Advocacy Centers, it’s become clear that it makes little sense to, in the short-term, push to open such a facility in each county. Rather, the group has focused on making sure that facilities are as accessible as possible to as many children who need them.

Some small counties just won’t have enough cases of alleged abuse to justify a Children’s Advocacy Center, he said.

Rumburg said the approach makes sense to her and seems to follow practices used by other social service groups. For instance, there are only 50 rape crisis centers to serve the state’s 67 counties, she said.