Many people have no idea how to use their thermostats — and it’s costing them

Published 6:00 am Wednesday, July 8, 2015

- Many people have no idea how to use their thermostats — and it's costing them

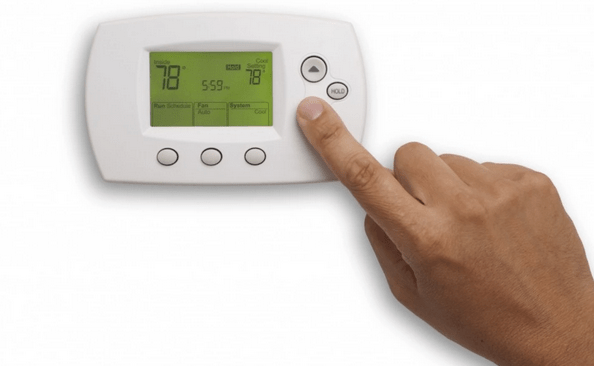

With Americans cranking up their air conditioning to bear the summer heat, it’s time to talk about those confusing little devices on the walls of your home: thermostats.

Home heating is the single largest source of power consumption in the home, and air conditioning comes in third. Thermostats control both. So simple changes in thermostat usage — lowering the air conditioning when you’re away at work during the day, to give just one example — could add up to significant savings. And a so-called “programmable thermostat” — which allows you to enter timed temperature settings — could, in theory, make that automatic and effortless.

But it turns out that many of us don’t have a clue what we’re doing with these devices, according to new research.

A study just out in the journal Energy Research and Social Science captures just how widely programmable thermostats are apparently being misused by their owners. Similar conclusions have been reached before — I wrote about prior research on the subject in November. However, the authors used a novel methodology — getting research subjects to upload photos of their thermostats — that further cemented the point.

“The responses to this survey paint a remarkable picture of a technology that is widely misunderstood by its users,” note the study authors, led by Marco Pritoni of the Western Cooling Efficiency Center at the University of California, Davis.

Out of 192 people surveyed, 42 percent of respondents said their thermostats were programmable — rather than manual — but many did not seem to know how to use them. 14 percent of those claiming to have programmable thermostats said they “do not know where the settings are” while another 25 percent said they “know where the settings are but [they] do not know how to change them.”

The uploaded pictures — which were provided by 30 out of 192 research subjects, who were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk — documented more problems. “About one third of the thermostats were in ‘permanent hold’ mode; this mode interrupts all the programs and turns the programmable thermostat into a manual thermostat,” the authors noted. And for most of these people, no help was coming — a 70 percent majority of all respondents, and 67 percent of respondents who said they did not know how to program their thermostats, also did not know where the thermostat manual was.

Other problems, meanwhile, included thermostats whose time and date settings were way off — making it hard to program timed behavior — and multiple people in the home being involved in setting the thermostat.

Meanwhile, people also demonstrated broad misconceptions about how thermostats — and indoor temperatures — actually work. Over a third wrongly believed that “setting the thermostat at a higher temperature would heat the house faster.” A similar proportion believed in the myth that “turning down the thermostat at night or when people are not at home used more energy than keeping the house at the same temperature all the time.” The truth, the authors explain, is that the home loses less heat to the outside in winter when the heat is set lower, meaning this folk notion is incorrect.

The research certainly raises doubts about the number of Americans who not only have a programmable thermostat to begin with (rather than a manual one), but also successfully and deliberately use it in such a way as to reduce their energy use. “These considerations confirm that the installation (and presence) of a programmable thermostat does not assure that it will be programmed to automatically set back the temperature,” noted the authors.

The research underscores at least two major conclusions.

First, the human element of energy use — the way that people behave with energy systems, as technology collides with psychology — remains a major factor in determining why we use as much as we do and, ultimately, emit as much carbon dioxide as we do. And even though we may have the right technologies to enable dramatic cuts in energy usage, it doesn’t matter if people don’t know how to use them.

Second, this research suggests that the makers of a new wave of “smart” thermostats, like Google’s Nest, have a wide opening. A thermostat that learns a person’s routines, and uses subtle cues to help them save energy, may be able to accomplish more than programmable thermostats that many people have trouble operating. And most recently, Nest has begun implementing sophisticated “demand response” programs that could further save energy — and users’ money — by automatically using less power at times of peak demand on the grid.

But the problem, says lead study author and energy efficiency expert Marco Pritoni of the University of California, Davis, is that these newer thermostats are not yet present in most homes. So for now, many people are still working with the older kinds of thermostats.

“I’m not sure that we’re going to see a global effect of the new technologies until they become the majority,” Pritoni says.